Content Warning: This article discusses historical events involving executions and the Nazi regime’s use of capital punishment, which may be distressing. It aims to educate on the mechanisms of state terror and the importance of justice, encouraging reflection on human rights and the dangers of authoritarianism.

Johann Reichhart (1893–1947), Germany’s last state executioner, served during the Nazi era, guillotining over 3,000 people from 1933 to 1945, including political dissidents, Jews, and others targeted by the regime. From a family of eight generations of executioners, Reichhart’s role transformed from a stigmatized profession to a tool of Nazi control. Joining the Nazi Party in 1937, he became indispensable in enforcing fear through public spectacles. This analysis, based on verified sources like Wikipedia and historical accounts from the Bavarian State Archives, provides an objective overview of Reichhart’s life, career, and the ethical complexities of his service, fostering discussion on the weaponization of law and the value of human rights.

Family Legacy and Early Career

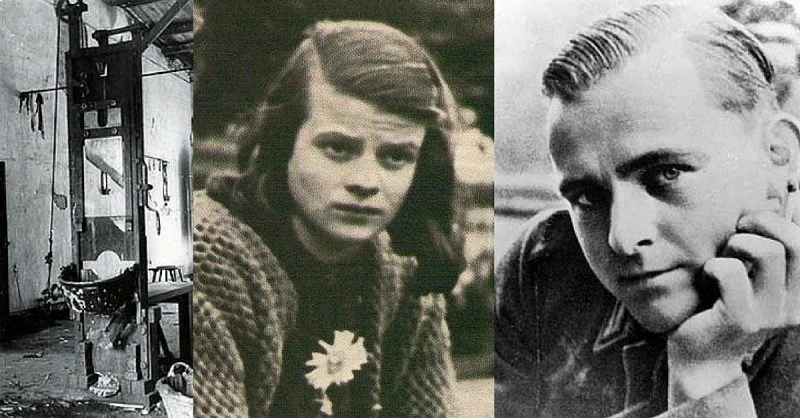

Johann Reichhart was born on February 20, 1893, in Haarbach, Bavaria, to a lineage of executioners dating back to the 17th century. His father, Johann Nepomuk Reichhart, held the post in Bavaria from 1907 to 1921. The profession, once shunned and hereditary, involved guillotining, a method introduced in Bavaria in 1813. Young Johann apprenticed under his father, learning the trade’s mechanics and rituals.

After World War I (1914–1918), where he served briefly, Reichhart took over as Bavaria’s executioner in 1921 at age 28, earning 100 Reichsmarks per execution. The Weimar Republic (1918–1933) saw limited use of capital punishment, but Reichhart executed 316 people by 1933, including murderers and political criminals.

Rise Under the Nazis

Adolf Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor on January 30, 1933, expanded the death penalty to suppress dissent. The Nazis passed laws like the Malicious Practices Act (March 1933), enabling executions for “political crimes.” Reichhart secured a contract with the Bavarian Ministry of Justice that year, guaranteeing steady pay and elevating his status from outcast to state servant.

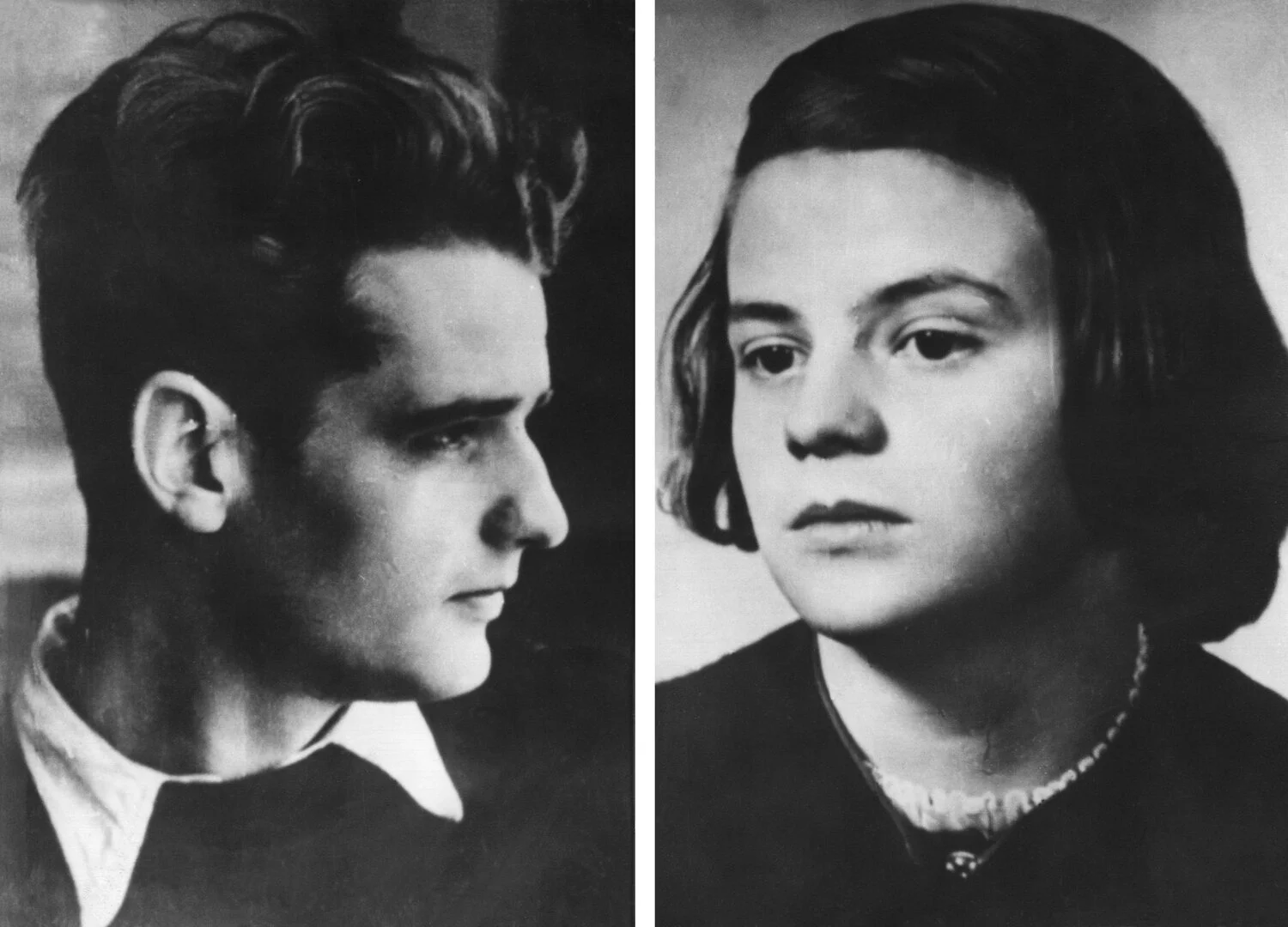

Executions became public propaganda, filmed for newsreels to instill fear. Reichhart guillotined high-profile victims, including Marinus van der Lubbe for the Reichstag fire (1933) and Sophie Scholl of the White Rose (1943). By 1937, he joined the Nazi Party (membership 5,598,304), aligning with the regime. His efficiency—executing up to 80 in a day at Brandenburg-Görden prison—made him the Third Reich’s most active executioner, responsible for 2,484 deaths from 1933 to 1945, plus 500 pre-Nazi.

Methods and Psychological Toll

Reichhart used the guillotine, a swift but terrifying device, for beheading. Executions were ritualized: prisoners walked to the scaffold, heads positioned under the blade, falling in 0.05 seconds. Despite the speed, Reichhart claimed moral detachment, viewing it as duty. Post-war, he expressed regret for executing innocents like the White Rose students but justified his role as obedience.

The Nazi system weaponized him; political purges, including the Night of the Long Knives (1934) and resistance members, filled his ledger. Women and youth executions rose, with 250 women guillotined, including resisters like Else Uhl (1943).

Post-War Trial and Death

After Germany’s surrender in May 1945, Reichhart was arrested by U.S. forces but released in 1946 after denazification, classified as a “follower.” He lived quietly in Altötting, Bavaria, until his death from natural causes on May 3, 1947, at age 54. No trial for his executions occurred, as he was seen as a tool, not a decision-maker.

Legacy and Reflection

Reichhart’s career highlights the normalization of violence under totalitarianism. His 3,000+ executions made him a symbol of Nazi terror, yet his post-war freedom raises questions of justice. Historians like Richard J. Evans note executioners like him as cogs in the regime’s machine, their remorse selective.

For scholars, Reichhart’s story underscores law’s perversion and the need for ethical boundaries.

Johann Reichhart’s life as Bavaria’s executioner, guillotining 3,000 under Nazi rule, reflects the regime’s use of fear as control. From family trade to party member, his service enabled purges and Holocaust-related killings. For history enthusiasts, his untried death prompts reflection on accountability, human rights, and discrimination’s dangers. Verified sources like Wikipedia ensure accurate remembrance, urging vigilance to prevent such state-sponsored terror.